The Case of the Missing Documents

How 30 boxes of documents vanished in plain sight. This is the 2nd installment in my series of research blog posts about the poet, scholar, and activist Genevieve Taggard.

In archive libraries, tension exists between sound and silence. Pages rustle, librarians murmur, carts rattle, the occasional researcher lets out a sigh. The documents themselves, while aurally quiet, are loud with information—text, images, data—that speaks of the past.

A core part of my Stamps project is learning how to engage with archives, from understanding how to effectively search in huge databases to using microfilm to handling fragile scraps of acidic paper. As I sift through Genevieve Taggard’s papers, I’m asking questions about her life and writing, but also about the archive itself. What sparked its creation? Why is it at Dartmouth? Who had a hand in its formation and maintenance? When I began this project a year ago, I thought these would be among the most simple questions of the ones I posed. But more often than not, the archive has been very quiet about its creation, evading my attempts to build a definitive narrative of its existence.

In the first installment of this research blog, I discussed canonical silences—how almost all poets who wrote between 1900 and 1950 have been forgotten, with the exception of a handful of big-name high modernists. Taggard and other “social poets,” who wrote about social issues with an eye to collectivity and revolutionary change, have been silenced by a conflation of factors, from economic influences on publishing and academia to misogyny and McCarthyism. This blog post deals with another type of silence: archival silence.

Marlene Manoff writes “For archivists, archival silences refer to gaps or omissions in a body of original records. For digital humanists, archival silences often refer to materials that are not available in formats useful for scholarly research” (Manoff 64). Manoff distinguishes between “gaps or omissions in a body of original records”—documents whose non-existence creates a hole in the record—and “materials that are not available” in useful formats, which do exist but remain inaccessible to researchers. I want to add a third type of silence, that around how documents were collected, organized, and cataloged, as well as who did that archival labor. This third silence is sometimes hard to identify, since we often conceive of archives as static and unchanging, and of archivists as passive and impartial agents. It is, however, critical to grapple with this third type of silence, since archives are subject to biases and change.

I’ve encountered a lot of archival silence while sorting through the Taggard Papers. In one case in particular, I’ve had to work out which of Manoff’s silences I am dealing with—omission or inaccessibility—and in doing so have found that these types of silences are often inextricably linked with silences around the formation of an archive. Struggling through these silences has pushed me to think deeply about how archives come to be, and what their creation means for the work of interpreting their contents. This post attempts to sift through some of that learning by walking you through this past summer’s archival mystery: The Case of the Missing Documents.

The Missing Documents

In his article on forms of power in archival work, Randall C. Jimerson brings up a scene from Star Wars II: Attack of the Clones, to explain how the archive, often presented as "comprehensive" and static, is often instead a site of incompletion and erasure. Here's that scene:

Jimerson's point is that “the archivist's pose of omniscience is truly an illusion,” and he urges archivists to be mindful of the ways they use their power when approaching questions of control and completion (21). I bring this scene up because this past summer, I was confronted with a similar, mysterious archival silence—documents that should exist but have vanished—and, often, a similar sentiment from the library staff: “If an item does not appear in our records, it does not exist.”

The items in question include hundreds of literary magazines from the early 20th century, sheets of music, concert programs, newspaper clippings, photographs, a vinyl record, and other miscellaneous objects related to Taggard’s life.

I first realized these objects were missing when I started to read through the correspondence between Kenneth Durant, Taggard’s second husband, and librarians at Dartmouth College in the mid-1940s, including H.G. Rugg, Alexander Laing, and Edward C. Lathem. I was attempting to find out why Taggard’s archive landed at Dartmouth and what implications that history has for my work with the documents. I’ve been able to piece together a somewhat incomplete timeline.

In 1944, Taggard fell ill, showing symptoms of underlying hypertension (Wald 232). A year later, Durant first queried Mr. Rugg about the possibility of establishing a complete collection of Taggard’s works, which were, in their present location at the couple’s home, “subject to the fire hazard of a Vermont farmhouse.” Durant’s goal was to have a copy of every poem and book that Taggard had published during her life contained within one collection.

In the following two decades, that goal was largely accomplished. Durant sent hundreds of documents—mainly newspapers and magazines containing Taggard’s poems, along with books, broadsides, and other printed ephemera—to Dartmouth, working with the librarians there to catalog and sort the material into what would become the Taggard Collection. I don’t know much about Durant as a person, but while reading through his correspondence with the librarians at Dartmouth, I’ve drawn the conclusion that he was deeply meticulous, if not slightly obsessive, about preserving Taggard’s work. Most of his letters to librarians at Dartmouth are detailed lists of documents being sent and requests for copies of catalog cards, so he could keep track of what sources still needed to be tracked down. Here are a select few pages from those letters, so you can get a sense of both the volume of documents and attention to detail this project entailed:

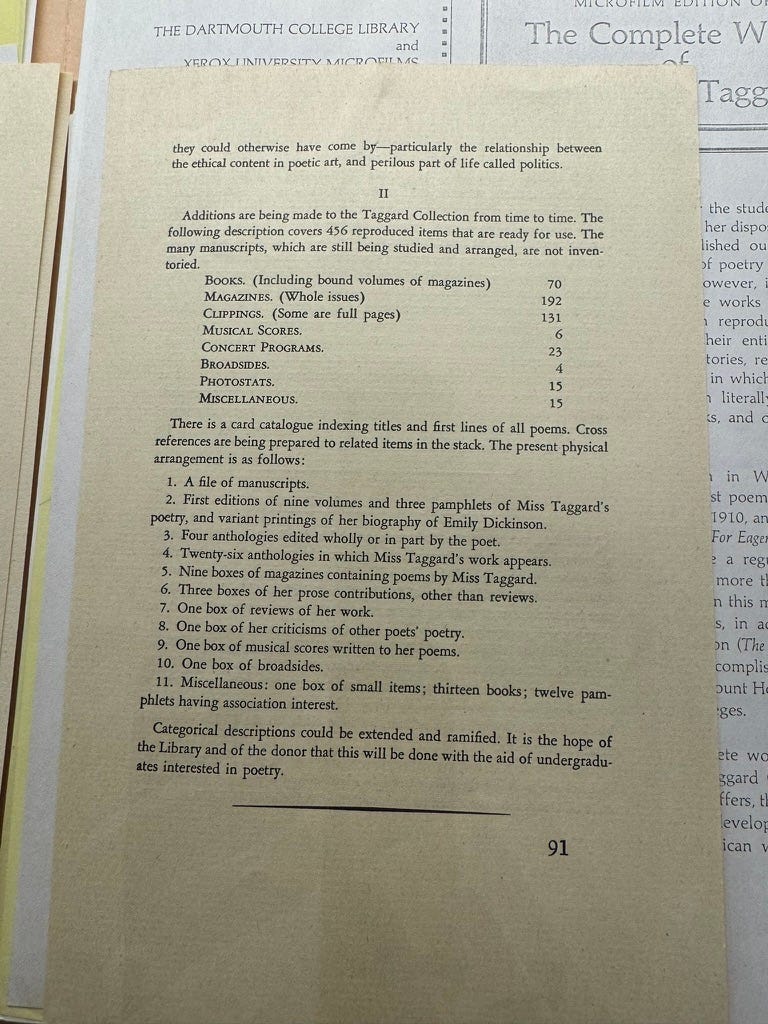

It was these sorts of letters and documents that first helped me realize that the 8 large archival boxes I had been sorting through for the past year—full of Taggard’s letters, manuscripts, printing proofs, and teaching materials—did not contain all of the documents that comprised the original collection. In fact, I quickly realized that most of the documents Durant had sent over were nowhere to be found in the catalog records for the materials that comprise Dartmouth’s Taggard Papers. In fact, the original collection boxes, reported in Dartmouth’s library bulletin in 1947, bore no resemblance to the organization of the current archive.

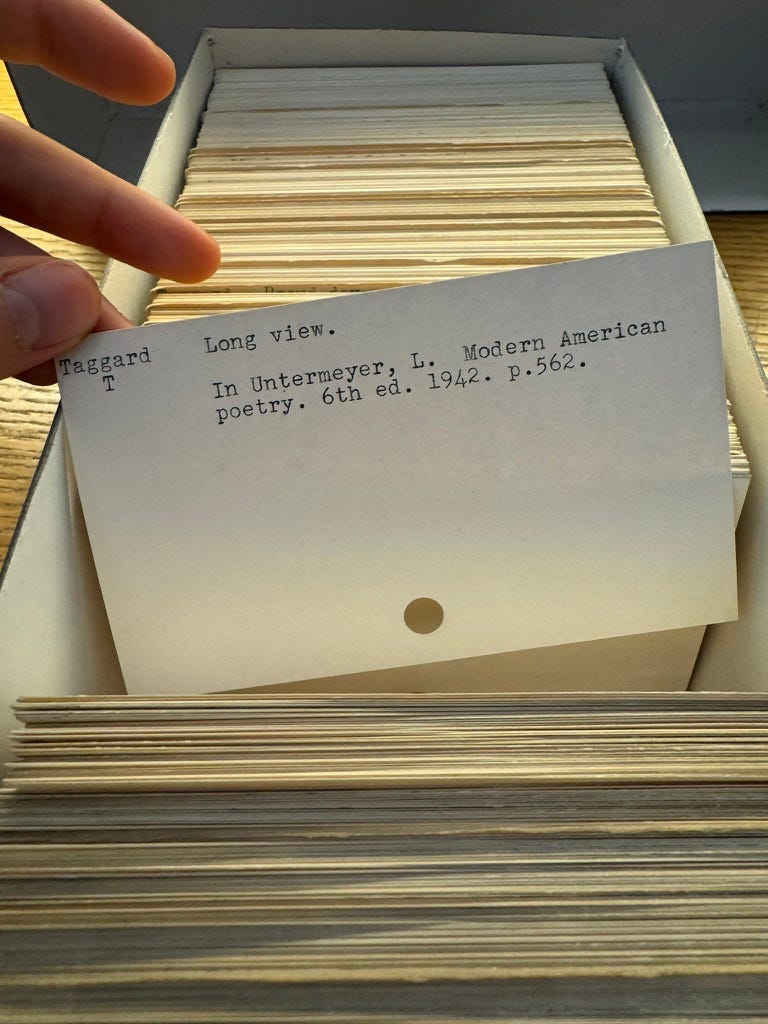

Beyond the surface level intrigue of missing materials, I really wanted a few specific documents that were supposed to be housed in Taggard’s collection, according to Durant’s letters and the original card catalog of items. One of these documents is a letterpress broadside of the poem “Long View,” printed for the poet’s friends and family as a Christmas gift in 1940. (I discuss “Long View” in detail in my first blog post). As a letterpress printer myself, I wanted to see this broadside, both to further my understanding of that poem’s history and so that I could potentially replicate the format of the broadside for a printing event at Dartmouth as a way to promote my research and Taggard’s life to students here. I was also interested in seeing the copies of UC Berkeley’s student paper, The Occident, which Taggard helped edit and published in extensively in the early 1920s. These newspapers haven’t been digitized like some of the later papers Taggard wrote for, so without access to them via Dartmouth’s collection, I was out of luck for laying eyes on her earliest works.

The Search

I started my hunt for these missing materials by asking the very helpful librarians at Rauner if I was missing something, or if they knew where these papers might be hiding. I stumped four different librarians and started a collection-wide search for these papers. But after a few days, each librarian came up empty-handed. Ultimately, they told me it was likely that most of the papers I was looking for had been thrown away during a reorganization of the collection, or sent to another institution.

I wasn’t going to take that for an answer, not without documentation of the downsizing or relocation, which the collection record didn’t have. My archival 6th sense was telling me we were missing some piece of information that would point to where these documents went. I went to visit Wendel Cox, the English Librarian, who is always my go-to source for very hard to find information. Wendel validated my suspicion that the documents had not been sent away or destroyed, and pointed me toward a new set of data related to the archive: microfilm.

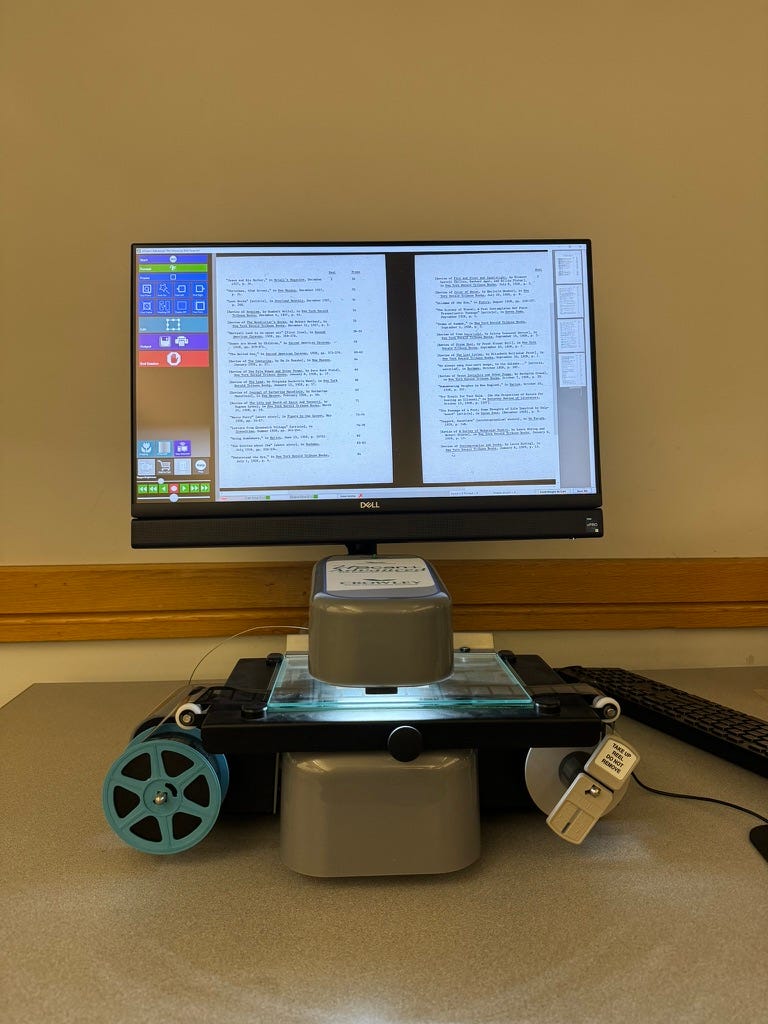

My project is all about exploring different methods and tactics for archives research, and figuring out how to use microfilm was a big moment of learning for me. The Taggard collection microfilm project began in 1970, when Kenneth Durant, still alive at the time, agreed to have the collection converted to microfilm. The project was completed at the end of 1971. More than 50 years later, I checked out the three boxes of film from the library reserves, unsure of what they contained and hoping I could find images of the broadsides and those early student publications.

After a few minutes of fumbling with equipment and then, luckily, help from a few more wonderful librarians, I got the microfilm up on the screen. (This was one of the most technically challenging things I have had to do for this project). The first many pages was a table of contents for the documents in the film, and I quickly realized that the reels, while important, didn’t have the documents I was after. This microfilm project ran parallel to the original archive’s goal of documenting each instance of Taggard’s poems in print. The microfilm has scans of each book, and of the first appearance in print of each poem. It does not, sadly, have complete scans of each magazine in which the poems appear, or scans of materials like broadsides, manuscripts, or letters that are also a significant part of an archive. So, while valuable on its own for documenting Taggard’s publication history and a near-complete set of her poems, the microfilm didn’t lead me closer to the missing documents.

It did, however, help me help me build more of a timeline for the missing documents. Some of the poems scanned into the microfilm did come from the missing magazines, so I knew that as late as 1971, the documents still existed in the Dartmouth collection. This also helped me determine that the missing materials weren’t thrown out in a large batch before that date. The 8 boxes of materials that comprise the current archive were put together in July of 1986, so that gave me a range of 15 years in which this disappearance took place.

Having checked all the archival boxes I had access to; online records; multiple card catalogs; multiple librarians; the archival collection and correspondence records for the Taggard Papers; the microfilm; and digital archives at other institutions for the missing documents, I was stuck. I consigned myself to the fact that I might never see the documents I was searching for, or solve the mystery of those missing boxes and files.

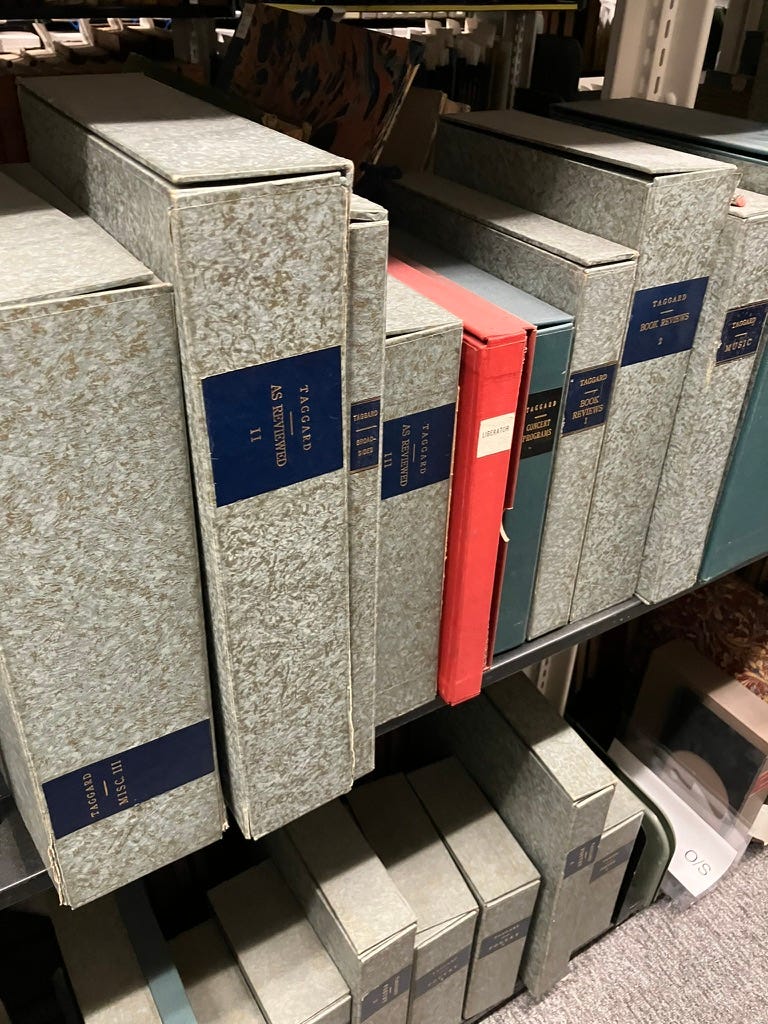

Then, I got an email. “Found the magazines!” wrote Jay Satterfield, the head of special collections at Rauner. And sure enough, hidden in plain sight on a shelf in the Oversize section of the special collections shelves were almost 30 boxes of Taggard material—all the papers, photos, and magazines Durant and others spent so much time collecting and organizing.

Archival Memory

So what happened? How does a library lose 30 boxes of documents within their own stacks? And what does this tell us about the nature of archival silence?

I don’t have all the answers, but much of this mystery seems tied to a reorganization of the Taggard archive that took place in July 1986. The note about this reorganization reads “Recently the decision was made to separate the manuscripts from the book collection, and to reorganize the papers for more efficient access by scholars.” When sorting through the documents to complete this process, archivists focused on letters, manuscript drafts, teaching materials, and other sources they thought would be of most interest to researchers. The removed and cataloged the books in the collection separately. That the third category of items in the old collection—the full runs of magazines and other small printed ephemera—were neglected. They didn’t make it into new boxes. And, more importantly, they didn’t make it into the paper finding aid that was eventually digitized and became the current, online finding aid.

During the reorganization, the importance of reading a poet’s early writings and magazine publications within the full context of the magazine in which they appear was devalued. This reflects the tendencies of New Criticism to isolate poems or other writing from their political and social contexts. In the current landscape of literary scholarship, those contexts are becoming more important—so regaining access to Taggard’s magazine publications, broadsides, and vinyl recordings feels exciting and valuable.

Reading poems in context lets us ask more questions about dialogue between different authors in the same magazine and about editorship and who was making decisions about what work was published. It allows us to ask about the design and physical production of the magazine, about it’s circulation within the public, the public’s response to different poems and articles. Even small elements of a magazine, like the paid advertisements on the back cover, give insight into the cultural atmosphere in which the poem was originally written, printed, and received. Having the full magazine versus having just the printed text of one poem in, say, a microfilm scan, is sort of like the difference between going to a national park and seeing a picture of it online. There’s a tangibility and fullness to the experience of picking up a vintage magazine that is almost impossible to replicate.

Modern archives rely on sophisticated digital catalog systems to location information and collections within a vast archive. In this case, the missing boxes had never been converted to the digital platform, making them nearly impossible to locate within the organizing system of the library shelves. As much as archives rely on technology, they also rely on human memory. My hypothesis is that when the 1986 collection reorganization was carried out and a new finding aid constructed for those documents, the librarians in Rauner knew that not all the documents pertaining to Taggard were in those archives. They would have been able to point interested scholars toward the other boxes as well. But over time, this knowledge of the extra boxes slipped away as folks retired or left Rauner. Librarians working at Rauner today didn’t know that those archives still existed.

For me, this mystery has highlighted the importance of understanding that our information technology systems are not absolute, and that human memory plays a huge and important role in the preservation of archival documents and collections. If even one librarian or staff member at Rauner had stumbled across those boxes, realized what they were, and filed that information away in their memory, I wouldn’t be writing this blog post. But archives are never that easy; even the head librarians in Rauner don’t know everything the collection holds. Happily, through this process, I’ve helped bring these boxes back into the working memory of the library staff. (Hopefully this blog post serves as useful documentation as well).

To close, I want to return to Manoff’s definition of archival silences and my addendum of a third silence around creation. The first type, the “gaps and omissions,” was the conclusion the librarians assisting me eventually came to about this missing documents. Given the limitations of technology and archival memory, I’m not surprised that this was the type of silence that was easiest to believe was occuring. The second type, “materials that are not available,” better describes the situation and captures my attitude toward this mystery. I was pretty sure the documents existed; I just couldn’t figure out where they went. Eventually, these two types of archival silence were broken. The situation now falls into the third type, silence about archival creation and maintenance. Without detailed records about the reorganization, and as time eroded the collective working memory of the librarians in Rauner, silence slipped over the collection.

Silence and memory continue to shape the ways I approach this work. A central goal for my research is building stronger collective memory around Taggard’s poetry and her life. Sometimes, like looks like posts that focus on specific poems (more coming soon). Sometimes, that looks like bringing her up in my classes or writing final papers on her poetry, even if she hasn’t been taught in the course. And sometimes, that looks like chasing down hidden boxes, even when I’ve been told they no longer exist.

My hope is that through these blogs and my work, I can help slow Taggard’s slide into archival oblivion by helping to break the silences that time, society, and the archive have imposed upon her life and work.

Citations

Jimerson, Randall C. "Embracing the Power of Archives," The American Archivist, 69, no 1, 2006, pg. 19-32. https://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article/69/1/19/24067/Embracing-the-Power-of-Archives

Laing, Alexander. “The Taggard Collection.” Dartmouth College Library Bulletin, February 1947. https://archives-manuscripts.dartmouth.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/295477.

Manoff, Marlene. "Mapping archival silence: technology and the historical record," in Engaging with Records and Archives, Facet, 2016, pg. 63-82. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/CBO9781783301607A013/type/book_part

Wald, Alan M. "Sappho in Red," in Exiles from a Future Time: The Forging of the Mid-Twentieth-Century Literary Left, University of North Carolina Press, 2002, pg. 229-261.